The elephant got in the room and never left (2021)

1. The elephant got in the room and never left, 2021.

installation view

2. Re/reunion (I,II,III,IV,V), 2021.

Porcelain

33x11x10 cm.

3. Biggest fear, 2021.

Porcelain and brass

5x4x5 cm.

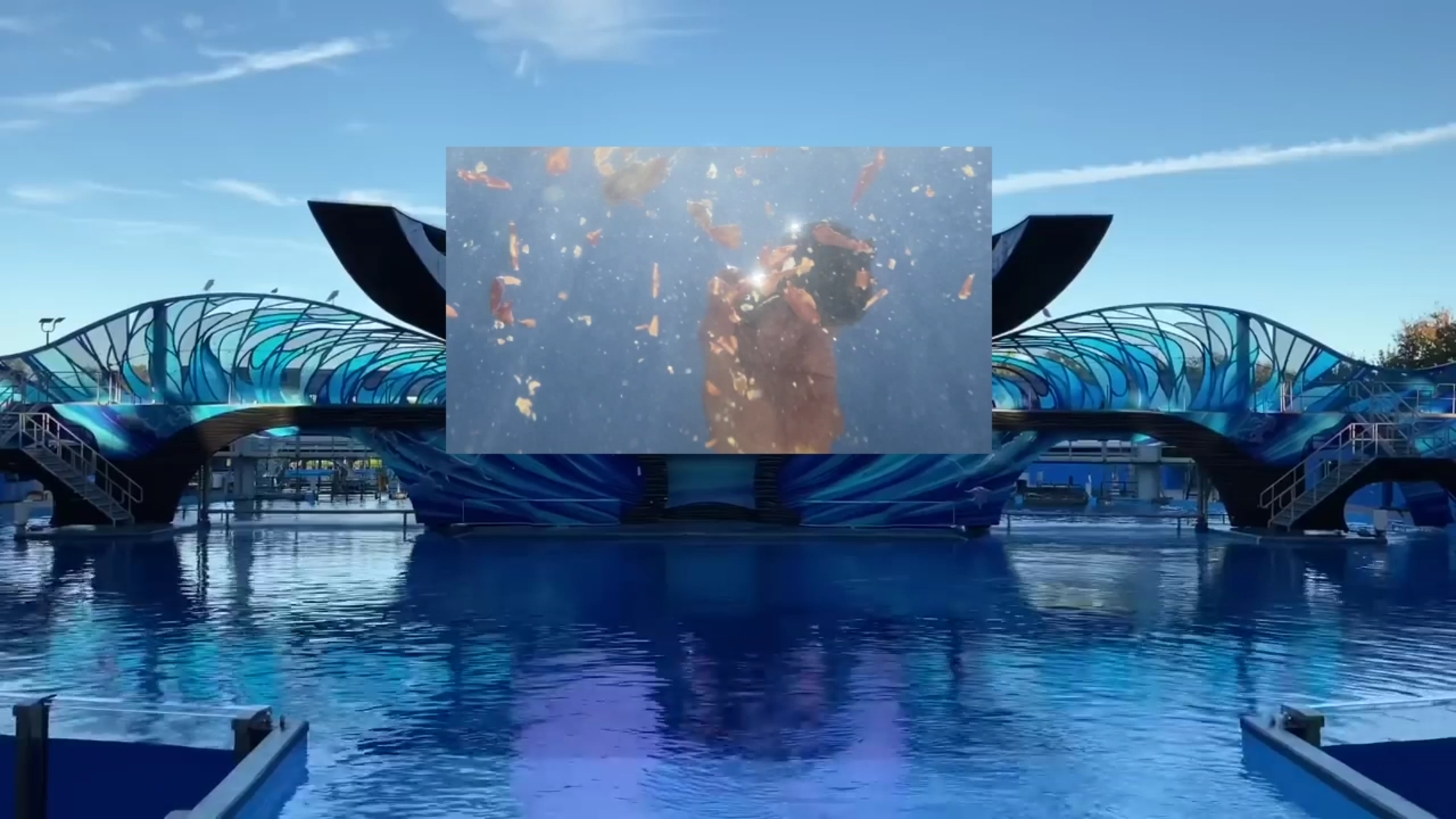

4. Apnea, 2021

7,53 min.

5. Elephant in between, 2021.

Porcelain

11x550(avarage length of an elephant)x33 cm.

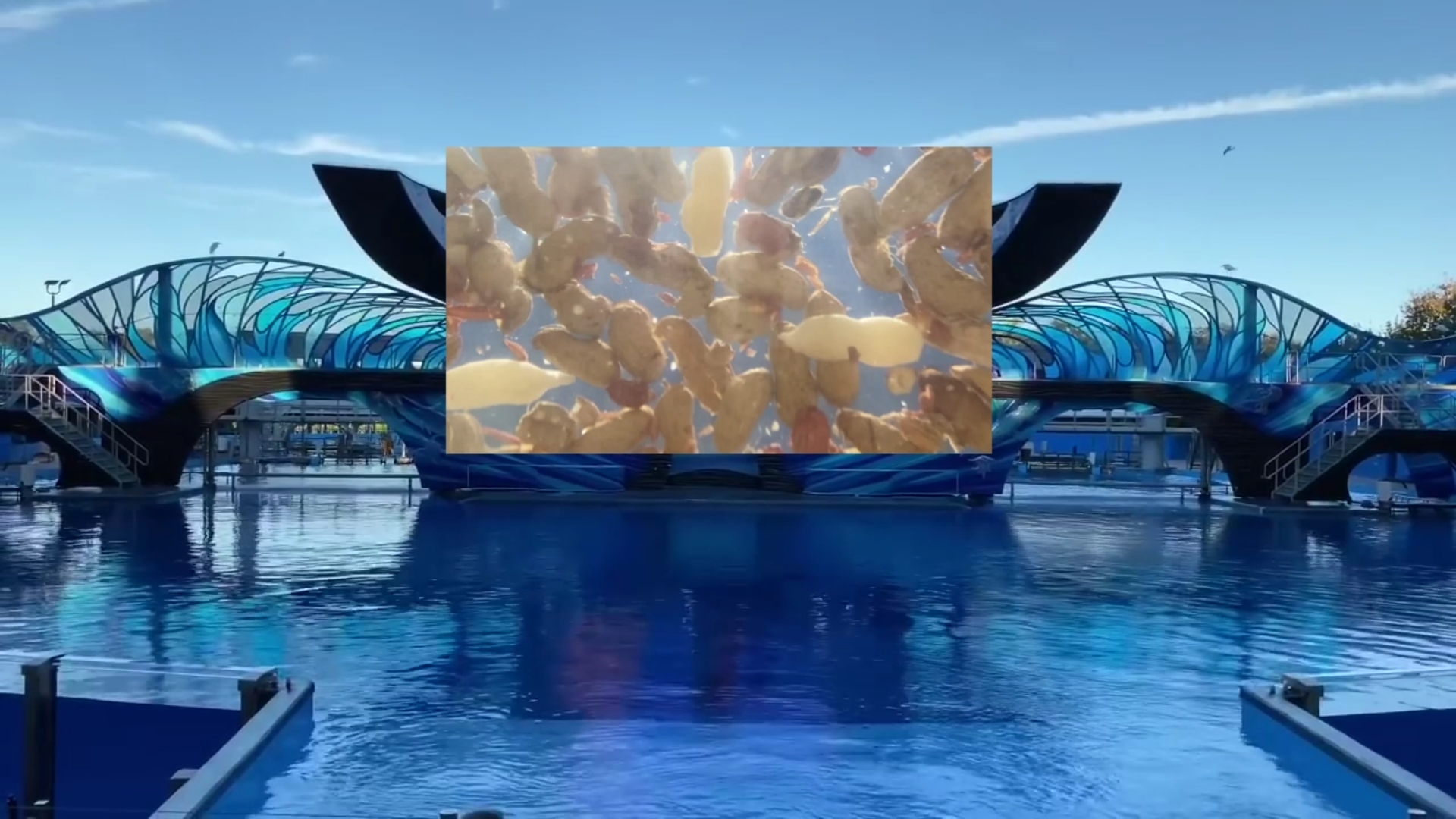

6. A coin, for a peanut, for a ringing bell: a coin, for a peanut, for a ringing bell; 2021.

Porcelain and paraffin

variable dimentions

7. The only way is through, 2021.

Paraffin

320(avarage height of an elephant)x100x3 cm.

Solo show at Duplex Air

THE ELEPHANT GOT IN THE ROOM AND NEVER LEFT (PT)

O cheiro é forte, o ruído é alto. Andamos entre pernas de elefantes, ninguém as vê.

A prática artística de Francisco Trêpa traduz-se numa abordagem transdisciplinar que tenta materializar as articulações, frequentemente complexas, entre o animal humano e o animal não-humano, atravessando realidades de conquista, enclausuramento, especismo e exibicionismo.

Nesta exposição, apresenta uma instalação que emprega elementos significantes de uma prática de exploração animal que remete para o Zoo de Lisboa: um espetáculo que foi, durante as décadas de 1980 e 1990, uma forte atração de obrigatória paragem para crianças e adultos, tendo-se tornado, desde então, uma memória coletiva de quem por lá passou. O espetáculo consistia numa troca caracterizada por uma espécie de tríade comercial: o visitante atirava uma moeda para o fosso da jaula, o elefante recebia um amendoim e, na sequência, tocava um sino (A coin, for a peanut, for a ringing bell: a coin, for a peanut, for a ringing bell). Este é, talvez, o mote principal para as obras que aqui se apresentam, resultando (estas) em materializações que, não só refletem um problema concreto de exploração animal, sempre dissimulado, como ainda têm a capacidade e abertura de apontar o espectador para questionamentos das mais diversas ordens.

A ironia resultante de uma subversão é constante nestas peças. A escultura The only way is through, feita com 1700 amendoins de parafina reproduzidos individualmente, lembra a estrutura das cortinas comummente colocadas em portas e passagens na tentativa de bloquear a entrada de insetos voadores. Construída através de uma lógica de armadilha: pela função de isco atribuída aos amendoins, pelo material que simula cera de abelha (parafina) e pela desproporção existente entre a altura da cortina e respetiva largura, a passagem que aqui vemos revela-se paradoxal, sendo, simultaneamente, atrativa e impossível.

Este jogo disfuncional e repetitivo, que tenta alterar e subjugar a naturalidade de uma espécie à imagem de outra (estreitando-a, por exemplo), é também evidenciado pela dimensão das peças que sugerem a forma de uma tromba de elefante, reduzidas à escala humana a partir de uma máscara de fantasia. Sob diferentes configurações e convocando-nos para tópicos distintos, todas apresentam um denominador comum: a porcelana. Pensando nas possibilidades discursivas da porcelana enquanto material – branco e irreversível – e nas referências a especismo nesta exposição, existe, aqui, um ponto de tangência indissociável: o de um sistema “fino”, antiquado, hierárquico e discriminatório. Mais: o de um sistema que, por vezes, nos deixa escapar a fragilidade e o vazio oco do seu interior. É o caso de Re-reunion, um ajuntamento intencionalmente circular que nos pode apontar para um diálogo íntimo sobre as reuniões de culto dos elefantes.

Uma antiga parábola proveniente de um texto budista, conta-nos a história de um grupo de pessoas que, não sabendo que de um elefante se trata, o tentam apreender e conceituar através do toque, com os olhos vendados. Cada pessoa sente uma parte diferente do corpo do elefante, levando-a a descrevê-lo com base numa experiência limitada e parcial, resultando em opiniões distintas entre cada uma. Em algumas versões, as pessoas começam a suspeitar umas das outras e acabam por entrar em conflito. Direta à moral da história, esta é a de que temos a tendência para reivindicar a verdade absoluta apenas com base numa parte de um todo, num ponto de vista, ignorando as experiências de outras pessoas e não fazendo um esforço pela compreensão partilhada da totalidade do que é posto em causa. É difícil não pensar nesta história ao experienciar Elephant in between, duas peças que fixam os limites do comprimento médio de um elefante na parede, insistindo para a sua presença no espaço, como dois fragmentos que nos instigam a preencher o espaço in between, a completar um espaço que parece ausente, na tentativa de uma apreensão total da sua dimensão.

São integradas ações do espetáculo inicialmente referido (entretanto abolido, segundo novas políticas europeias que obrigavam a mostrar ao público uma “maior naturalidade dos animais neste contexto”) num ecrã de um outro espetáculo tão disseminado e atualmente recorrente pelo mundo, o dos animais marinhos. O vídeo Apnea parece apontar-nos para uma situação igualmente obsoleta num contexto de práticas atuais de Zoos, refletindo assim o absurdo desta normalização.

Restar-me-á referir o seguinte: existe uma permanente dimensão de teatralidade no Zoo que é também percetível nesta exposição, através de associações mais diretas, como em Apneia, ou de associações mais subtis, como a da instalação The only way is through à própria cortina de teatro (enquanto elemento separador de ator e espectador, de palco e plateia). Neste sentido, talvez seja importante mencionar o conceito de teatro aplicado ao Zoo, de John Berger (1926-2017), que implica pensar e definir, numa lógica intercambiável, um palco, uma plateia, os atores e os espectadores deste contexto. Ora, sabemos que os animais olham, com frequência, os visitantes. Percebemos, também, que o papel dos visitantes pode ser comparado ao de uma atuação pela sua previsibilidade: deambular e observar os animais. Se assim for, coloca-se então a questão: quem é que observa? (Who’s Watching?) E quem é observado? Acedendo para lá das aparências e tentando apreender todo o “elefante”, quem são, afinal, os atores e os espectadores deste estranho espetáculo?

Beatriz Coelho, junho 2021

THE ELEPHANT GOT IN THE ROOM AND NEVER LEFT

The stench is strong, the noise is loud. We are walking between elephants´ legs but nobody sees them.

Francisco Trêpa's artistic practice translates into a transdisciplinary approach that tries to materialize the often complex articulations between the human animal and the non-human animal, while crossing realities of conquest, confinement, speciesism and exhibitionism.

In this exhibition, he presents an installation employing significant elements of an animal exploration practice that can be traced back to the elephants pit at the Lisbon Zoo in the late 80s and early 90s. The ringing bell ‘trick’ was a well disseminated attraction and a mandatory stop for children and adults, having since become a sort of collective memory shared by those who visited the zoo in that period. The spectacle consisted of an exchange forged by a kind of commercial triad: the visitor threw a coin into the cage pit, the elephant received a peanut, and then rang a bell (A coin, for a peanut, for a ringing bell: a coin, for a peanut, for a ringing bell). This dysfunctional repetition is what constitutes the method for the works presented here, resulting in materializations that not only reflect a concrete problem of animal exploitation (which is always disguised) but also have the capacity to tease the viewer into questioning their own impressions.

The irony resulting from this subversive humdrum becomes a constant. For instance, The only way is through was made with 1700 individually reproduced paraffin peanuts and resembles a type of curtain commonly placed on doors and passageways, acting as attempted blockades to flying insects. While seemingly inviting, it was built using the same logic of a trap employed at the zoo: the peanuts act as bait, the trickery is granted by paraffin, a material that simulates bees wax, the awkward disproportion between the height of the curtain and its width seems to draft the unfeasible task of fitting an elephant through a door. Thus, the passage we see here is somewhat paradoxical, being simultaneously attractive and impossible.

This interplay is also evidenced by the pieces suggestive of the shape of an elephant's trunk. Despite signalling trunk, we are immediately disconcerted by its human scale, which reveals the reductive nature of a novelty mask. Identical but displayed in various configurations, the hard but delicate trunks are calling us to consider different topics through their common denominator: porcelain. When thinking about the discursive possibilities of porcelain as a material – white and irreversible – and the references to speciesism proposed here, we are faced with another inseparable point of tangency: that of a “fine”, antiquated, hierarchical and discriminatory system which, at times, lets out the fragility and hollow emptiness of its interior. This is the case in Re-reunion, an induced circular formation that recalls the gatherings of mourning elephants.

There is a Buddhist parable that tells the story of a group of blindfolded people who, unaware of what an elephant is, attempt to apprehend and conceptualize it through touch. Each person feels a different part of the elephant's body, leading them to describe it based on a partial experience, resulting in different opinions. In some versions, people become suspicious of each other and end up in conflict. The moral of the story is that we tend to claim absolute truth based solely on parts of a whole, a point of view, while ignoring other people's experiences and not making an effort to understand the shared totality of what is called into question. It's hard not to think about this story when experiencing Elephant in between, two pieces that establish the limits of the average length of an elephant on the wall, insisting on conjuring its presence in space, like two fragments that urge us to fill the gap in between, to complete a space that seems to be absent, in an attempt to fully grasp its dimension.

The video Apnea, installed on the back wall, seems to encompass an equally obsolete activity in the context of current Zoo practices, that of marine animal shows, exposing the absurdity of its standardization. By integrating one of the main elements (peanuts) from the initially referred show into

the orca amphiteatre, the entire format is put into question. While these marine shows have been merely adapted, the peanut trick has been abolished altogether, according to new policies that bet on showing the public more ‘natural’ behaviours of animals.

Thus, there is a permanent dimension of theatricality in the Zoo that is also noticeable here. Sometimes through more direct associations, such as in Apnea, or more subtle associations, such as on The only way is through which could refer to the theatre curtain as a separating element between actor and spectator, stage and audience.

In Why look at animals John Berger proposed a theatrical optic applied to the Zoo, where definitions of stage, audience, actors and spectators are made somewhat interchangeable, in order to be accessed critically. We know that animals often look at visitors. We also know that the role of a visitor is decidedly active: it involves walking around and observing the animals. If so, the question arises: (who’s watching?) who in this “weird theatre”? More so, while reaching beyond appearances in the attempt to apprehend the entirety of an elephant, are there definitive actors and spectators on this twisted show?

Beatriz Coelho, June 2021